|

I’m not the Bishop.

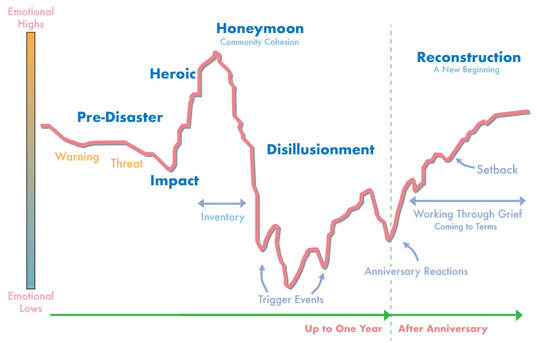

And rarely would I suggest myself as an alternative to Bishop Gates’ preaching. The events that have taken place after he recorded his sermon: George Floyd’s death and the subsequent wave of violent protests across the country have made the need for a live sermon more urgent and more immediate. I want to take a step back and tell you where I think we are as a county. This slide – ah, the advantage of online worship – shows the arc of emotional health during the lifecycle of a disaster. You see the moment of impact, followed by the heroic phase. Everyone wants to do well and rise to the occasion. This lasts for a while, and then We fall off the cliff into disillusionment as the reality of the situation sinks in. In the case of covid-19, the heroic phase may be corollated to the stay at home orders and most people making that sacrifice of working from home, online schooling, and only going out for essential services and items. Now, with 40 million people unemployed, no national plan for managing the pandemic, and social distancing and masks the best we have to slow the spread at the moment, with the prospect of the economic aid packages expiring, and the threat of evictions looming, I think we’re in the disillusionment phase. Eventually, we will get back to where we were emotionally, but this one is likely to be a while. This is the context in which George Floyd’s death happened. As a First Responder Chaplain, I am outraged by the actions of the four individuals responsible for his death and by their callous indifference to human life. They will have to answer for their actions and face the consequences. The actions of these four individuals revealed, unabashedly, the sin of racism, personal and institutionalized, of our country. And they show, in all its ugliness, the consequences of demonizing and dehumanizing ‘the other’. The protesters are legitimately angry about Mr. Floyd’s death. And they should be. We all should be. And about Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, and Christian Cooper, and all the people whose lives have been damaged, diminished, or ended by racism. Reacting with violence, though, is not the answer. Reacting by vilifying the police in general, is not the answer. Rage and Violence will not end racism by themselves. Instead, I think that we as Grace church are called to work with others to dismantle the edifice that creates and perpetuates institutional racism. We, as members of Christ’s body, are called to respond. First, we are called to look at ourselves and assess whether we. Knowingly or not, are racist in any way. If we are, we need to stop it and begin over so that we aren’t. That’s the first step. The second is to work with others. We have reached out to the president of our local NAACP chapter to see how we can support them and work together; we are convening the Burgess Committee to formulate a meaningful response, and we are reaching out to the Diocese and the wider Church to see how we can help. As a start on this Pentecost Sunday – the day when the Spirit of God ignited and inspired the disciples to spread the message of God’s unyielding and unending love for each person, black, brown, yellow, red, white, - everyone. – I want to read Presiding Bishop Michael Curry’s Word to the Church that he issued yesterday: It’s called When the Cameras are Gone, We Will Still Be Here[1] May 30, 2020 “Our long-term commitment to racial justice and reconciliation is embedded in our identity as baptized followers of Jesus. We will still be doing it when the news cameras are long gone.” In the midst of COVID-19 and the pressure cooker of a society in turmoil, a Minnesota man named George Floyd was brutally killed. His basic human dignity was stripped by someone charged to protect our common humanity. Perhaps the deeper pain is the fact that this was not an isolated incident. It happened to Breonna Taylor on March 13 in Kentucky. It happened to Ahmaud Arbery on February 23 in Georgia. Racial terror in this form occurred when I was a teenager growing up black in Buffalo, New York. It extends back to the lynching of Emmett Till in 1955 and well before that. It’s not just our present or our history. It is part of the fabric of American life. But we need not be paralyzed by our past or our present. We are not slaves to fate but people of faith. Our long-term commitment to racial justice and reconciliation is embedded in our identity as baptized followers of Jesus. We will still be doing it when the news cameras are long gone. That work of racial reconciliation and justice – what we know as Becoming Beloved Community – is happening across our Episcopal Church. It is happening in Minnesota and in the Dioceses of Kentucky, Georgia and Atlanta, across America and around the world. That mission matters now more than ever, and it is work that belongs to all of us. It must go on when racist violence and police brutality are no longer front-page news. It must go on when the work is not fashionable, and the way seems hard, and we feel utterly alone. It is the difficult labor of picking up the cross of Jesus like Simon of Cyrene, and carrying it until no one – no matter their color, no matter their class, no matter their caste – until no child of God is degraded and disrespected by anybody. That is God's dream, this is our work, and we shall not cease until God's dream is realized. Is this hopelessly naïve? No, the vision of God’s dream is no idealistic utopia. It is our only real hope. And, St. Paul says, “hope does not disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts by the Holy Spirit” (Romans 5:5). Real love is the dogged commitment to live my life in the most unselfish, even sacrificial ways; to love God, love my neighbor, love the earth and truly love myself. Perhaps most difficult in times like this, it is even love for my enemy. That is why we cannot condone violence. Violence against any person – conducted by some police officers or by some protesters – is violence against a child of God created in God’s image. No, as followers of Christ, we do not condone violence. Neither do we condone our nation’s collective, complicit silence in the face of injustice and violent death. The anger of so many on our streets is born out of the accumulated frustration that so few seem to care when another black, brown or native life is snuffed out. But there is another way. In the parable of the Good Samaritan, a broken man lay on the side of the road. The religious leaders who passed were largely indifferent. Only the Samaritan saw the wounded stranger and acted. He provided medical care and housing. He made provision for this stranger’s well-being. He helped and healed a fellow child of God. Love, as Jesus teaches, is action like this as well as attitude. It seeks the good, the well-being, and the welfare of others as well as one’s self. That way of real love is the only way there is. …Opening and changing hearts does not happen overnight. The Christian race is not a sprint; it is a marathon. Our prayers and our work for justice, healing and truth-telling must be unceasing. Let us recommit ourselves to following in the footsteps of Jesus, the way that leads to healing, justice and love. On this Pentecost Sunday. The day on which God’s Spirit of love animated the disciples and spread throughout the earth. * On this day of Pentecost. On the day on which God's love for everyone was made manifest. Let us recommit to following in the footsteps of Jesus. The way that leads to healing, justice, and love. [1] Presiding Bishop Curry’s Word to the Church: When the Cameras are Gone, We Will Still Be Here, Michael Curry, May 30, 2020. Downloaded May 31, 2020 from https://episcopalchurch.org/posts/publicaffairs/presiding-bishop-currys-word-church-when-cameras-are-gone-we-will-still-be-0

1 Comment

|

The Reverend Stephen Hardingis the Rector Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed