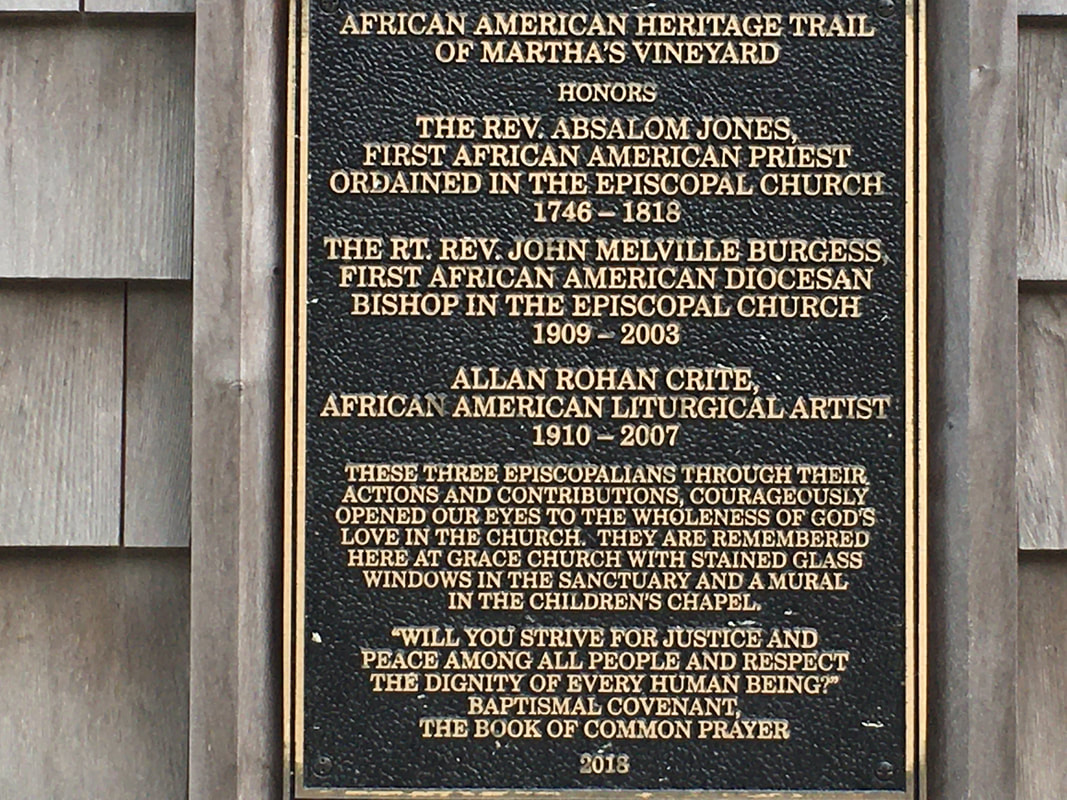

Grace Church is honored to be

Site #28 on

the African American Heritage Trail of Martha's Vineyard

Honoring

The Reverend Absalom Jones

The Right Reverend John Melville Burgess

Allan Rohan Crite

|

Visit the

African American Heritage Trail of Martha's Vineyard for or more on our site and the other sites on the trail. Each of these three African American Episcopalians, through their actions and contributions, have courageously opened our eyes to the wholeness of God's love in the church. They are remembered here at Grace Church with stained glass windows in the sanctuary and a mural in the Children's Chapel.

|

The Reverend

|

The Right Reverend

|

From Grace Church's Description of Reverend Jones and Bishop Burgess

To celebrate the life of the Right Reverend John Melville Burgess in 1999, Grace Church commissioned stained glass artist Lyn Hovey to design a pair of lancet windows showing Absalom Jones on the left and Bishop Burgess on the right. According to the artist, "As men of African descent, each broke the color barrier to attain a priestly office that no African descendant had previously held in the United States."

Above the Reverend Absalom Jones is a smaller picture of Jones "kneeling in prayer with his friend Richard Allen in 1787. The setting is a humble blacksmith's shop they rented for services, after leaving St. George's Methodist Episcopal Church, in protest over being segregated during a worship service.

Pictured above the Right Reverend John Burgess is the chancel of St. Paul's Cathedral in Boston. The contrast between the blacksmith's shop and St. Paul's Cathedral is an illustration of the breadth of the vineyard in which these two disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ have labored."

Bishop Burgess was a spokesperson for equal rights, for human rights, for justice and the word of God. He and his wife, Esther Taylor Burgess, an activist in her own right, mo ved to martha's Vineyard and became members of Grace Church in 1989. They were members of the Martha's Vineyard Chapter of the NAACP and also the Union of Black Episcopalians.

Above the Reverend Absalom Jones is a smaller picture of Jones "kneeling in prayer with his friend Richard Allen in 1787. The setting is a humble blacksmith's shop they rented for services, after leaving St. George's Methodist Episcopal Church, in protest over being segregated during a worship service.

Pictured above the Right Reverend John Burgess is the chancel of St. Paul's Cathedral in Boston. The contrast between the blacksmith's shop and St. Paul's Cathedral is an illustration of the breadth of the vineyard in which these two disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ have labored."

Bishop Burgess was a spokesperson for equal rights, for human rights, for justice and the word of God. He and his wife, Esther Taylor Burgess, an activist in her own right, mo ved to martha's Vineyard and became members of Grace Church in 1989. They were members of the Martha's Vineyard Chapter of the NAACP and also the Union of Black Episcopalians.

The Reverend Absalom Jones

Absalom Jones' Biography as proposed to the 2022 General Convention of the Episcopal Church(1):

His Feast Day is February 13.

Absalom Jones was born enslaved to Abraham Wynkoop, a wealthy Anglican planter in 1746 in Delaware. He was working in the fields when Abraham recognized that he was an intelligent child and ordered that he be trained to work in the house. Absalom eagerly accepted instruction in reading. He also saved money he was given and bought books (among them a primer, a spelling book, and a bible). Abraham Wynkoop died in 1753, and by 1755 his younger son Benjamin had inherited the plantation. When Absalom was sixteen, Benjamin Wynkoop sold the plantation and Absalom’s mother, sister, and five brothers. Wynkoop brought Absalom to Philadelphia, where he opened a store and joined St. Peter’s Church. In Philadelphia, Benjamin Wynkoop permitted Absalom to attend a night school for black people operated by Quakers following the tradition established by abolitionist teacher Anthony Benezet.

At twenty, with the permission of their masters, Absalom married Mary Thomas, who was enslaved to Sarah King, who also worshipped at St. Peter’s. The Rev. Jacob Duche performed the wedding at Christ Church. Absalom and his father-in-law, John Thomas, used their savings and sought donations and loans primarily from prominent Quakers, in order to purchase Mary’s freedom. Absalom and Mary worked very hard to repay the money borrowed to buy her freedom.

They saved enough money to purchase property and to buy Absalom’s freedom. Although he repeatedly asked Benjamin Wynkoop to allow him to buy his freedom, Wynkoop refused. Absalom persisted because as long as he was enslaved, Wynkoop could take his property and his money. Finally, in 1784, Benjamin Wynkoop freed Absalom by granting him a manumission. Absalom continued to work in Wynkoop’s store as a paid employee.

Absalom left St. Peter’s Church and began worshipping at St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church. He met Richard Allen, who had been engaged to preach at St. George’s, and the two became lifelong friends. Together, in 1787, they founded the Free African Society, a mutual aid benevolent organization that was the first of its kind organized by and for black people. Members of the Society paid monthly dues for the benefit of those in need.

At St. George’s, Absalom and Richard served as lay ministers for the black membership. The active evangelism of Jones and Allen significantly increased black membership at St. George’s. The black members worked hard to raise money to build an upstairs gallery intended to enlarge the church. The church leadership decided to segregate the black worshippers in the gallery without notifying them. During a Sunday morning service, a dispute arose over the seats black members had been instructed to take in the gallery. The ushers attempted to physically remove them by first accosting Absalom Jones. Most of the black members present indignantly walked out of St. George’s in a body.

Prior to the incident at St. George’s, the Free African Society had initiated religious services. Some of these services were presided over by The Rev. Joseph Pilmore, an assistant at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. The Society established communication with similar black groups in other cities. In 1792 the Society began to build the African Church of Philadelphia. The church membership took a denominational vote and decided to affiliate with the Episcopal Church. Richard Allen withdrew from the effort as he favored affiliation with the Methodist Church. Absalom Jones was asked to provide pastoral leadership, and after prayer and reflection, he accepted the call.

The African Church was dedicated on July 17, 1794. The Rev. Dr. Samuel Magaw, rector St. Paul’s Church, preached the dedicatory address. Dr. Magaw was assisted at the service by The Rev. James Abercrombie, assistant minister at Christ Church. Soon thereafter, the congregation applied for membership in the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania on the following conditions: 1) that they would be received as an organized body; 2) that they would have control over their local affairs; 3) that Absalom Jones would be licensed as lay reader, and, if qualified, be ordained as a minister. In October 1794, it was admitted as the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. The church was incorporated under the laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1796. Bishop William White ordained Jones as deacon in 1795 and as priest on September 21, 1802.

Jones was an earnest preacher. He denounced slavery and warned the oppressors to “clean their hands of slaves.” To him, God was the Father, who always acted on “behalf of the oppressed and distressed.” But it was his constant visiting and mild manner that made him beloved by his congregation and by the community. St. Thomas Church grew to over 500 members during its first year. The congregants formed a day school and were active in moral uplift, self-empowerment, and anti-slavery activities. Known as “the Black Bishop of the Episcopal Church,” Jones was an example of persistent faith in God and in the Church as God’s instrument. Jones died on February 13, 1818.

1) Biography from Satucket Lectionary's web page for the Rev'd Absalom Jones, accessed August 17, 2022, from http://www.satucket.com/lectionary/Absalom_Jones.htm

His Feast Day is February 13.

Absalom Jones was born enslaved to Abraham Wynkoop, a wealthy Anglican planter in 1746 in Delaware. He was working in the fields when Abraham recognized that he was an intelligent child and ordered that he be trained to work in the house. Absalom eagerly accepted instruction in reading. He also saved money he was given and bought books (among them a primer, a spelling book, and a bible). Abraham Wynkoop died in 1753, and by 1755 his younger son Benjamin had inherited the plantation. When Absalom was sixteen, Benjamin Wynkoop sold the plantation and Absalom’s mother, sister, and five brothers. Wynkoop brought Absalom to Philadelphia, where he opened a store and joined St. Peter’s Church. In Philadelphia, Benjamin Wynkoop permitted Absalom to attend a night school for black people operated by Quakers following the tradition established by abolitionist teacher Anthony Benezet.

At twenty, with the permission of their masters, Absalom married Mary Thomas, who was enslaved to Sarah King, who also worshipped at St. Peter’s. The Rev. Jacob Duche performed the wedding at Christ Church. Absalom and his father-in-law, John Thomas, used their savings and sought donations and loans primarily from prominent Quakers, in order to purchase Mary’s freedom. Absalom and Mary worked very hard to repay the money borrowed to buy her freedom.

They saved enough money to purchase property and to buy Absalom’s freedom. Although he repeatedly asked Benjamin Wynkoop to allow him to buy his freedom, Wynkoop refused. Absalom persisted because as long as he was enslaved, Wynkoop could take his property and his money. Finally, in 1784, Benjamin Wynkoop freed Absalom by granting him a manumission. Absalom continued to work in Wynkoop’s store as a paid employee.

Absalom left St. Peter’s Church and began worshipping at St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church. He met Richard Allen, who had been engaged to preach at St. George’s, and the two became lifelong friends. Together, in 1787, they founded the Free African Society, a mutual aid benevolent organization that was the first of its kind organized by and for black people. Members of the Society paid monthly dues for the benefit of those in need.

At St. George’s, Absalom and Richard served as lay ministers for the black membership. The active evangelism of Jones and Allen significantly increased black membership at St. George’s. The black members worked hard to raise money to build an upstairs gallery intended to enlarge the church. The church leadership decided to segregate the black worshippers in the gallery without notifying them. During a Sunday morning service, a dispute arose over the seats black members had been instructed to take in the gallery. The ushers attempted to physically remove them by first accosting Absalom Jones. Most of the black members present indignantly walked out of St. George’s in a body.

Prior to the incident at St. George’s, the Free African Society had initiated religious services. Some of these services were presided over by The Rev. Joseph Pilmore, an assistant at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. The Society established communication with similar black groups in other cities. In 1792 the Society began to build the African Church of Philadelphia. The church membership took a denominational vote and decided to affiliate with the Episcopal Church. Richard Allen withdrew from the effort as he favored affiliation with the Methodist Church. Absalom Jones was asked to provide pastoral leadership, and after prayer and reflection, he accepted the call.

The African Church was dedicated on July 17, 1794. The Rev. Dr. Samuel Magaw, rector St. Paul’s Church, preached the dedicatory address. Dr. Magaw was assisted at the service by The Rev. James Abercrombie, assistant minister at Christ Church. Soon thereafter, the congregation applied for membership in the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania on the following conditions: 1) that they would be received as an organized body; 2) that they would have control over their local affairs; 3) that Absalom Jones would be licensed as lay reader, and, if qualified, be ordained as a minister. In October 1794, it was admitted as the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. The church was incorporated under the laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1796. Bishop William White ordained Jones as deacon in 1795 and as priest on September 21, 1802.

Jones was an earnest preacher. He denounced slavery and warned the oppressors to “clean their hands of slaves.” To him, God was the Father, who always acted on “behalf of the oppressed and distressed.” But it was his constant visiting and mild manner that made him beloved by his congregation and by the community. St. Thomas Church grew to over 500 members during its first year. The congregants formed a day school and were active in moral uplift, self-empowerment, and anti-slavery activities. Known as “the Black Bishop of the Episcopal Church,” Jones was an example of persistent faith in God and in the Church as God’s instrument. Jones died on February 13, 1818.

1) Biography from Satucket Lectionary's web page for the Rev'd Absalom Jones, accessed August 17, 2022, from http://www.satucket.com/lectionary/Absalom_Jones.htm

The Right Reverend John Melville Burgess

Bishop Burgess' Biography is from "The Church Awakens: African Americans and the Struggle for Justice's Leadership Page (2):

Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Burgess earned his bachelor’s degree in 1930 and a year later his master’s degree in sociology, both from the University of Michigan. He continued his education at the Episcopal Theological School in Cambridge, Massachusetts and graduated in 1934.

After his ordination the following year, Burgess returned to Michigan and ministered to working class parishes in Michigan and Ohio during the Great Depression and WWII. From 1946 to 1956, he served as the Episcopal chaplain of Howard University where he was named the first black canon at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. in 1951. He used the national pulpit to assert a voice for human and civil rights.

Five years later Burgess returned to Boston as archdeacon of the city’s missions and parishes and superintendent of the Boston City Mission. After restructuring the organization as a catalyst for change rather than a social services provider, he renamed it Episcopal City Mission. He worked to develop an urban mission strategy at the parish level and urged the involvement of city churches in the lives of the poor.

While working to improve urban ministry, Burgess was elected to the position of bishop suffragan of the Diocese of Massachusetts in 1962. Eight years later, he became the first African American to oversee white congregations upon his election as bishop coadjutor. After his assiduous work to empower minorities in the Church and make the Church more inclusive, Burgess retired in 1975.

Bishop Burgess was active in the National Council of Churches and the World Council of Churches and served the General Convention on numerous commissions and boards. He served as president of the Union of Black Episcopalians from 1979 to 1981. [Sources]

2) Accessed August 17, 2022 from https://episcopalarchives.org/church-awakens/exhibits/show/leadership/clergy/burgess

Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Burgess earned his bachelor’s degree in 1930 and a year later his master’s degree in sociology, both from the University of Michigan. He continued his education at the Episcopal Theological School in Cambridge, Massachusetts and graduated in 1934.

After his ordination the following year, Burgess returned to Michigan and ministered to working class parishes in Michigan and Ohio during the Great Depression and WWII. From 1946 to 1956, he served as the Episcopal chaplain of Howard University where he was named the first black canon at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. in 1951. He used the national pulpit to assert a voice for human and civil rights.

Five years later Burgess returned to Boston as archdeacon of the city’s missions and parishes and superintendent of the Boston City Mission. After restructuring the organization as a catalyst for change rather than a social services provider, he renamed it Episcopal City Mission. He worked to develop an urban mission strategy at the parish level and urged the involvement of city churches in the lives of the poor.

While working to improve urban ministry, Burgess was elected to the position of bishop suffragan of the Diocese of Massachusetts in 1962. Eight years later, he became the first African American to oversee white congregations upon his election as bishop coadjutor. After his assiduous work to empower minorities in the Church and make the Church more inclusive, Burgess retired in 1975.

Bishop Burgess was active in the National Council of Churches and the World Council of Churches and served the General Convention on numerous commissions and boards. He served as president of the Union of Black Episcopalians from 1979 to 1981. [Sources]

2) Accessed August 17, 2022 from https://episcopalarchives.org/church-awakens/exhibits/show/leadership/clergy/burgess

Allan Rohan Crite, 1910 - 2007

African American Liturgical Artist

From Grace Church's Description of Allan Rohan Crite

In the 1950's the Reverend Tom Lehman, former Rector of Grace Church, commissioned Allan Crite to pain the mural in the Children's Chapel. The mural is typical of Crite's work which often depicted religious themes in ordinary life. Crite rejected the stereotypical views of African Americans and instead sought to paint people of color as everyday human beings.

The Mural in the Children's Chapel portrays the Vineyard Haven harbor as it was seen in the 1950s, with a gathering of children shepherded by religious figures at the feet of a luminous Christ.

The Mural in the Children's Chapel portrays the Vineyard Haven harbor as it was seen in the 1950s, with a gathering of children shepherded by religious figures at the feet of a luminous Christ.

Allan Rohan Crite

From the Smithsonian American Art Museum (3):

Allan Rohan Crite (born Plainfield, NJ 1910–died Boston, MA 2007)

Allan Crite was a painter, illustrator, librarian, and writer whose work explored the African American experience in and around Roxbury, Massachusetts, the Boston neighborhood where he lived almost his entire life.

He attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and spent one year as a Works Project Administration (WPA) artist. In 1940, he took a job as a draftsman for the Boston Ship Yard, a position he held for thirty years. He later worked as a librarian at Harvard University. While working, he attended Boston University and the Massachusetts College of Art before completing his studies at Harvard University.

Crite created art and literary works inspired by Negro spirituals, religious themes, and his neighborhood, saying that he had three aims: to focus on “black people in this city as I saw them,” to convey “the idea of the spirituals,” and to tell “the story of man using the black figure.”

As a self-described “artist reporter,” Crite said his neighborhood paintings aimed to “establish a record, just to show the life of black people in an ordinary setting—to show them ‘just as people’ and not a social problem.”

3) Accessed August 16, 2022 from https://americanart.si.edu/education/oh-freedom/allan-rohan-crite

Allan Rohan Crite (born Plainfield, NJ 1910–died Boston, MA 2007)

Allan Crite was a painter, illustrator, librarian, and writer whose work explored the African American experience in and around Roxbury, Massachusetts, the Boston neighborhood where he lived almost his entire life.

He attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and spent one year as a Works Project Administration (WPA) artist. In 1940, he took a job as a draftsman for the Boston Ship Yard, a position he held for thirty years. He later worked as a librarian at Harvard University. While working, he attended Boston University and the Massachusetts College of Art before completing his studies at Harvard University.

Crite created art and literary works inspired by Negro spirituals, religious themes, and his neighborhood, saying that he had three aims: to focus on “black people in this city as I saw them,” to convey “the idea of the spirituals,” and to tell “the story of man using the black figure.”

As a self-described “artist reporter,” Crite said his neighborhood paintings aimed to “establish a record, just to show the life of black people in an ordinary setting—to show them ‘just as people’ and not a social problem.”

3) Accessed August 16, 2022 from https://americanart.si.edu/education/oh-freedom/allan-rohan-crite

O God, who created all peoples in your image, we thank you for the wonderful diversity of races and cultures in this world. Enrich our lives by ever widening circles of fellowship, and show us your presence in those who differ most from us, until our knowledge of your love is made perfect in our love for all your children;

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Episcopal Book of Common Prayer, Thanksgiving for the Diversity of Races and Cultures. p. 840.

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Episcopal Book of Common Prayer, Thanksgiving for the Diversity of Races and Cultures. p. 840.